Below is the text and illustrative slides for of the talk I gave at MLA 2012, entitled “What Can Digital Reading Tell Us About the Material Places of Victorian Poetry?” as part of a panel organized by Charles LaPorte on The Cultural Place of Nineteenth-Century Poetry.

My title has a number of key words in it that don’t typically appear together. About what I mean by digital reading I’ll have more to say in a moment; but embedded in the phrase is a tension between the cool machinery of processing units associated with the digital and the warm bodies and moist eyes that read. Most theories and methodologies of digital or computational text analysis have nothing to say about textual materiality, because they focus only on the linguistic elements of texts. And, despite the fact that two pioneering digital archive projects have focused on Blake and Rossetti, even the most sophisticated digital tools designed for use with literary texts have little to do with Victorian poetry‘s specific features

The digitization of public domain materials by research libraries, Google, and others has tremendously benefited us as scholars of the nineteenth-century cultural record. Perhaps the most obvious benefit appears as an increase in scale: rather than the hundreds of volumes of Victorian poetry owned by my library, I can now access many thousands.

Obviously, for certain kinds of research questions, there’s no substitute for access to the printed book, and to multiple copies of those books, as Andrew Stauffer has argued. Sometimes we need to handle the actual Victorian material objects.

But the large-scale digitization of Victorian texts offers us the opportunity of asking some new research questions and pursuing them in new ways that could both deepen and widen our historical understanding of Victorian culture.

DIGITAL READING

Franco Moretti’s use of the term distant reading intentionally positions large-scale statistical analysis (of book titles, of places mentioned in novels, and other kinds of data) as the opposite of the close reading that many literary scholars practice. Such binarization too easily maps onto others: between collaborative projects and individual insights, between new technologies and traditional methods, and between large prose texts and the short lyric poems favored by the New Critics. Although I’m sympathetic to much of Moretti’s work, the questions I’m interested in demand a more flexible negotiation and combination of the poles sketched by those oppositions.

So here’s how I’m currently defining digital reading:

methods of literary research and interpretation that draw upon computational analysis to move beyond human limitations of vision, memory, and attention

When literary scholars use the term reading – – especially in the formulations of close and distant – – we often conflate research and interpretation into one iterative and recursive activity. We already have hypotheses before we ever sit down to read a text, and our subsequent reading is in fact an initial testing of those hypotheses and an iterative rewriting of them as we encounter new information and notice new patterns. The development of humanistic knowledge depends upon this iterative, recursive blurring of the boundaries between hypothesis, data collection, experimentation, and analysis.

We call all of that reading.

In digital reading, this process is supported by the computer’s ability to count, store, recall, and display information in a variety of ways beyond what humans can do.

What I’m calling digital reading is closely aligned with what Stephen Ramsay has described as algorithmic criticism. However, professional reading (be it close, distant, or digital) is not the same thing as the rhetorical action of critique, so I think it might better be thought of as a precursor to the posing of critical arguments in settings like academic conferences.

THE MATERIAL PLACES OF POETRY

Poetry circulated in Victorian print culture in newspapers, weekly and monthly magazines, and in books priced for a variety of markets. As a starting point for this project, I’m primarily focusing on single-author books of poetry.

I’m experimenting with using computational tools to approach three aspects of the Victorian material text:

- bibliographic metadata (which describe the book as an object that exists in the world)

- graphic or visual elements (the interface of the book-object with the reader)

- the distribution of words within and across book-objects (which is always spatial as well as graphic and linguistic)

I. Books in the World

My work is rooted in Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of the cultural field of production, which focuses on the structural relations existing among various individual agents and cultural institutions at a particular historical moment. This field is constituted by what he calls “position-takings” – – all of the actions or decisions that produce a work of art and its cultural value.

The structures of cultural value that surrounded Tennyson’s In Memoriam, Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and Other Poems, or any other volume of Victorian poetry were partly created by all the other books of poetry, including what Bourdieu calls the “unremarked” ones that were overlooked by both Victorian critics and scholars in our own day.

So, in order to find out more about that cultural field, I’m creating a database of bibliographic metadata of single-author books of poetry published between 1840-1890. That’s a big project and I’m only just at the beginning. What I’m going to show you today is drawn from some initial feasibility testing of different sources and methods for collecting the data.

Bibliographic metadata describe the book as a physical object in the world. This includes citational information (author, title, publisher, place, date) as well as other information about the physical book (number of pages, presence of a preface or appendices), descriptive notes, or provenance information for a particular copy.

Library catalogs and enumerative bibliographies are good existing sources of this metadata, but they vary widely in what they record and how they present this information. For this project I’ll be drawing upon WorldCat and the British library catalog as well as Catherine Reilly’s bibliographies, the Cambridge Bibliography, and others.

In libraries following the Library of Congress system, most books of poetry are cataloged under author names, which are filed under national categories. If you know the names of the authors, then it’s easy to find their works. But it’s more difficult to start by looking for a specific genre, kind, or form of literature. In library catalogs, for instance, poetry is only going to show up in the metadata if words like poems, poetry, poets, or verse appear in a title, summary, or note. Books about poetry are easier to find than the books of poems themselves.

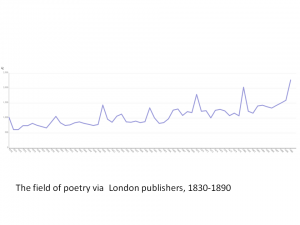

As part of some feasibility testing I’ve been doing, I’ve been gathering metadata from WorldCat, searching for verse, poems, and related keywords, but limiting my searches to London as the place of publication, and to English language books only. This data has not yet been fully cleaned, so these results include multi-author collections and also some books about poetry

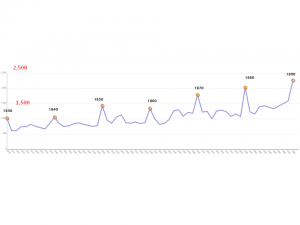

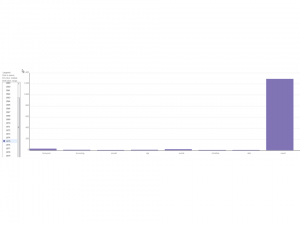

So this set of data is a messy, limited, and incomplete approximation of the literary field of poetry as represented by London publishers 1830-1890. But even so I think we can learn some things. This slide shows the total counts from that data for each year between 1830 and 1890.

(click to view images full size)

Overall, the graph shows an increase in poetry publishing as the century progresses, which isn’t surprising since the same is true of all publishing in the Victorian period.

Overall, the graph shows an increase in poetry publishing as the century progresses, which isn’t surprising since the same is true of all publishing in the Victorian period.

Seeing the the peaks and valleys on the graph, however, raises new questions about what they might represent. In particular, you might notice that there are substantial increases at each decade year:

This data set contains 784 items for 1849, and 1435 for 1850, an increase of 83 percent.

There’s an increase of 52% at the next decade year: 880 items for 1859 and 1341 for 1860, and almost the same percentage increase from 1869 (1181 items) to 1870 (1791).

The consistency of this pattern tells me that it means something – – even if I don’t yet know whether this is a feature of the metadata (i.e., books with approximate dating being grouped together into a decade by a librarian as 1830s) or whether it describes something about the historical context of poetry publishing. I think the answer lies somewhere in the middle, as a combination of both these factors.

Even if some percentage of those peaks are from catalogers’ estimations, it doesn’t explain the size of some of these increases, particularly as you move later in the period, when most published books have clear dates of publication.

What I want to know now (and will begin discovering) is what kinds of patterns can be found in the books published on the decade years as compared with other years.

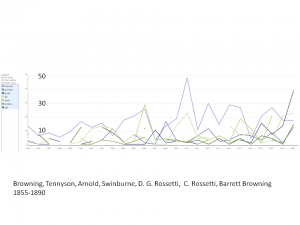

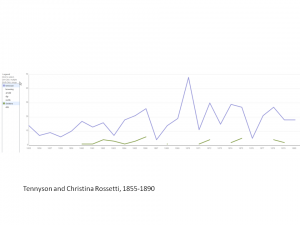

We can also track publications by specific authors. Here’s how seven major poets (Tennyson, Browning, Arnold, Dante Rossetti, Swinburne, Christina Rossetti, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning) are represented in this data set.

Such graphs are particularly helpful in visualizing the differences between those authors whose works were continually being reprinted, such as Tennyson, and those who intermittently appear in the cultural field, like Christina Rossetti.

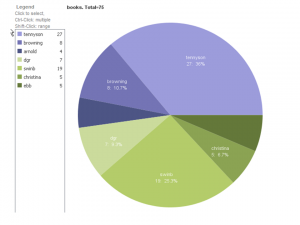

This next slide shows a synchronic slice for the year 1875 – – books by and about those seven major Victorian poets: Tennyson has 36%, Browning almost 11%, and Swinburne 25% of the total of 75. This is a snapshot of the Victorian poetry canon as it is frequently studied and taught.

And here’s the same year, 1875, as a bar graph showing those seven poets in comparison to the total count in this data set for that year.

To the left you can barely see the lines representing the seven poets I just showed you. It’s difficult to create visualizations of the data that will clearly show both the fractions for those canonical poets and the total number of items, because the numbers are so disparate. This slide shows just how small a percentage of the total publications in the year 1875 are by or about the poets we tend to focus on. (Again, keep in mind that this is an incomplete and uncleaned data set. In time I’ll have more accurate data, but I fully expect the general shape of those results to be similar.)

There’s so much that we don’t know about all the books represented in that space between the total number and the bars for the canonical poets. Gathering accurate metadata and building a database that we can query for meaningful patterns will I hope be a starting point for understanding the Victorian cultural field.

II. The Visual Page as Interface

All printed texts simultaneously convey meaning through both linguistic and graphic signs. As Jerome McGann suggests in Radiant Textuality,

“. . . text documents, while coded bibliographically and

semantically, are all marked graphically” (138)

and that

“A page of printed or scripted text should thus be understood as a certain kind of graphic interface.” (199)

Most scholarly digital archive projects today recognize the value of this graphical meaning and provide users access to both digitized page images and plain text versions of printed materials.

In books of poetry printed after 1800, the relative amount and distribution of white space on the page cues the reader to the presence of poetry.

Your eye can immediately perceive the difference between the page of a novel and a page of poetry.

The graphic conventions of line capitalization, punctuation, and indentation often signal and reinforce linguistic features of the poem.

Extra leading, or white space, between poetic stanzas and the indentation of poetic lines reinforce rhyme patterns and formal structures of specific verse forms like the sonnet, which was frequently surrounded by ample marginal space.

What I’m describing today is drawn from preliminary research I did towards a larger project which will (when we get grant support) develop a set of tools for the computational analysis of the graphic or visual elements in digitized printed books. Those tools will add machine-learning capabilities to the kinds of analysis I’m talking about today.

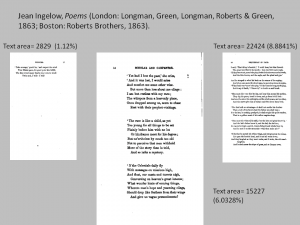

Here I’m using ImageJ, an open source program developed by the National Institute of Health, to calculate the text area of a page image, both as a numerical pixel count and as a percentage of the total page area in a data set of 75 single-author books of poetry published for the first time in the 1860s by 75 different authors. Some of these authors are long-canonical figures like Tennyson or Arnold; others like Dora Greenwell, Sarah Stickney Ellis, or Philip James Bailey have increasingly been brought to our attention in recent decades. And many others are virtually unknown to most of us today.

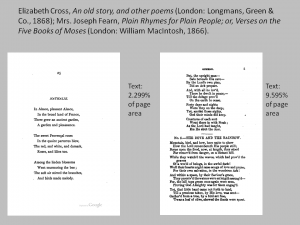

Using digital tools provides more specific ways of naming the difference that is obvious to our human eyes between text-sparse and text-dense page design exemplified here by a page from Elizabeth Cross’s An Old Story, in which text makes up just over 2% of the total page area, and Mrs. Joseph Fearn’s Plain Rhymes for Plain People, with nearly 10% of the page consisting of text.

Measuring text area on the page also can provide more concrete information about the range and average of text density within a given book.

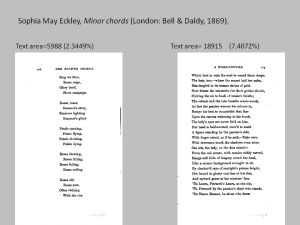

For instance, here are the pages in Sophia Eckley’s Minor Chords with the lowest and highest text density, (excluding title pages, table of contents, and half-titles).

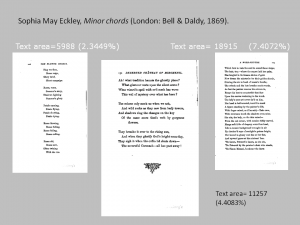

And here you can see what the average page in this book looks like.

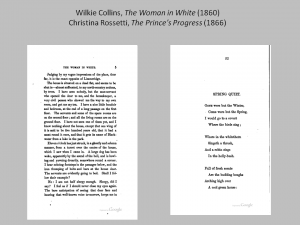

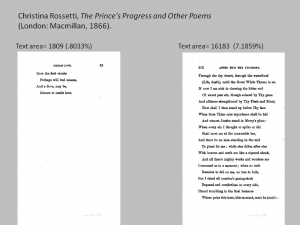

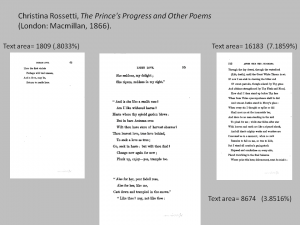

Here’s the same analysis of lowest and greatest text density for a book that’s more familiar to most of us, Christina Rossetti’s The Prince’s Progress and Other Poems:

Here is an average page in that book:

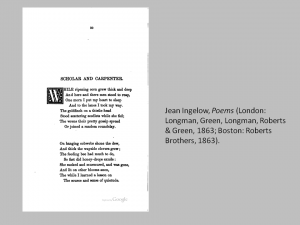

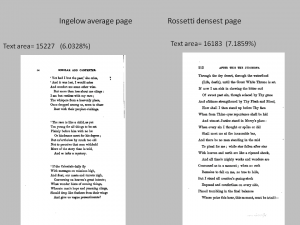

In Jean Ingelow’s Poems, we can see that the most dense pages are much more text-heavy than those in Rossetti or Eckley.

Significantly, the average page in this volume has a text covering 6.03% of the page, which is about double that of the average page in Rossetti’s book, and is mathematically fairly close to the densest page in Rossetti’s, which opens up comparative research questions about poetic form, aesthetics, and reading experience.

But I’m especially interested in what the computer can show me that I am less likely to perceive on my own.

Here I’m showing the same average Ingelow page on the left, with another one from the same book on the right.

Where my eye sees a lot of difference between these two pages (number of stanzas, line length, and indenting practices), mathematically they are very similar. So one of the things I’ll be exploring as this project moves forward is what constitutes significant statistical patterns in the graphic aspects of Victorian books of poetry. Digital analysis can help us move beyond our human assumptions and perceptions to understand the cultural record in new ways.

3. Textual Analysis

As a human reader, I can only hold a limited number of examples or texts in my mind at once. Digital text analysis tools can help us move beyond those limitations of memory and attention. Most of the large-scale projects interested in computational methods for text analysis are focused on prose texts. Even with very basic text string searching, an 800-page Victorian novel suddenly becomes available for different kinds of thematic or linguistic analysis than reading unassisted by a concordance or word index typically affords. At the level of scale, the payoff seems obvious. But the same is true for poetic texts. A work like Dante Rossetti’s poetic sequence The House of Life, which consists of 102 sonnets in the 1881 version, exemplifies this situation, as we continually negotiate between the condensed structure and expression of each individual sonnet to its placement in a sequence that has its own structure and significance.

I’ve been using a variety of text analysis tools to analyze the distribution of words in Victorian poems, in order to see what those tools can tell us about poetry, and also what poetry can tell us about those tools. Today I just have time to give a quick example from this work.

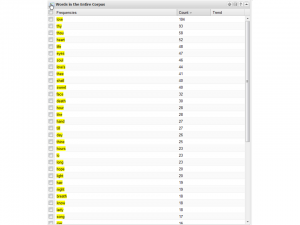

Computers are very good at counting: if we count the words in this 1881 text of The House of Life, with a standard stop word list applied to ignore “the” and other common particles, you can see that Love tops the list, followed by: thy, thou, heart, life, and eyes.

This fits with what we already know about the poem as an exploration “Of Life, Love, and Death” as one early version of The House of Life was titled.

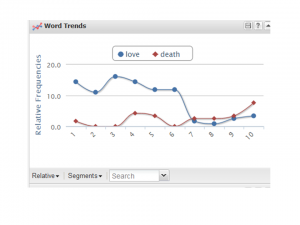

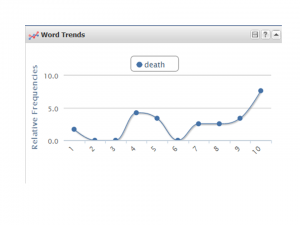

Using Stéfan Sinclair’s Voyeur Tools, you can also map the occurrence of particular words through a text or set of texts. This shows the word death mapped across the 102 sonnets of The House of Life:

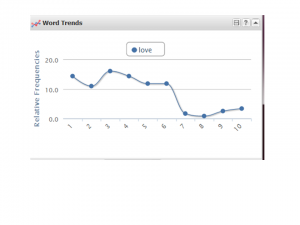

This is the graph for the word love:

This is the graph for the word love:

And for both of them:

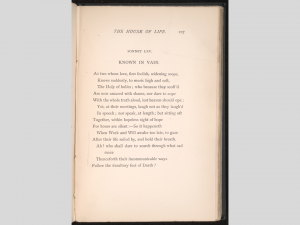

This graph points us to something that happens in this sequence at sonnet 65:

KNOWN IN VAIN.

As two whose love, first foolish, widening scope,

Knows suddenly, to music high and soft,

The Holy of holies; who because they scoff’d

Are now amazed with shame, nor dare to cope

With the whole truth aloud, lest heaven should ope;

Yet, at their meetings, laugh not as they laugh’d

In speech; nor speak, at length; but sitting oft

Together, within hopeless sight of hope

For hours are silent:–So it happeneth

When Work and Will awake too late, to gaze

After their life sailed by, and hold their breath.

Ah! who shall dare to search through what sad maze

Thenceforth their incommunicable ways

Follow the desultory feet of Death?

In typical Rossetti fashion, the syntax of this sonnet structures a densely-worded comparison: the crucial moment on which the comparison turns is enjambed forward from the sonnet’s traditional turn between lines 8 and 9 into the middle of line 9, typographically and syntatically doubly marked with colon and dash:

For hours are silent:–So it happeneth

All that discussion of the lovers is to get us to understand this:

. . . –So it happeneth

When Work and Will awake too late, to gaze

After their life sailed by, and hold their breath.

The sonnet describes how this happens as a complex arrangement of amazement and shame leading to a kind of abashed silence, the tempering of the laughter and speech of early love into silence:

. . . sitting oft

Together, within hopeless sight of hope

This particular sonnet is never really about love: the discussion of the lovers simply provides a kind of template for understanding the retrospective melancholy investigation performed by Work and Will, Rossetti’s personifications of drive and intention within the poem. This moment that the sonnet ostensibly describes – – of waking and gazing too late upon the course of one’s life – – initiates a sequence of sonnets within the series that take up the challenge offered by the final lines:

Ah! who shall dare to search through what sad maze

Thenceforth their incommunicable ways

Follow the desultory feet of Death?

After this sonnet, the tone and focus of The House of Life sequence changes, navigating an interior reflective psychological landscape.

Now, I’m not the first scholar to notice the importance of this sonnet, and you don’t need a word map to realize something interesting happens here in the series. You could read that something thematically, as I just did, without having seen the graph.

But the graph pointed me here; it helped me see that this sonnet marks an important juncture in the series as a whole. I now read the sad maze as describing the remainder of the House of Life that follows. Here, however, is always material, a physical location in this particular book, as well as a moment in the sonnet series.

This image from the Rossetti Archive gives a bit of the sense of the physical location of page 227 in a book of 336 pages of poetry, as the remaining leaves are just visible past the edge of the page. Digital reading of literary texts should, I argue, combine attention to the linguistic text with attention to the material.

CONCLUSION

Our method, quite simply, as literary scholars, is to pay attention to patterns. Digital tools offer us computational power for conducting analysis far beyond our human limitations. Such tools can offer us new ways of understanding the material places of Victorian poetry through analyzing patterns in the metadata, page images, and linguistic layers of the digitized text. I believe such analysis might transform our historical understanding of poetry’s circulation, function and effects in the Victorian period.